Working with distributed systems introduces unique challenges; nowhere is this more obvious than transactions. When your application spans multiple services, they might be deployed as independent Kubernetes pods. Determining whether you’re dealing with a genuine distributed operation can be incredibly tough. It requires careful coordination or a race condition that needs a different resolution approach.

This ambiguity often leads to subtle bugs, data inconsistencies, and a debugging nightmare. In this post, I want to demystify some of these complexities. I will also share how the Spring Boot framework can be instrumental in taming these distributed beasts. It is complemented by powerful tools like Hibernate’s optimistic and pessimistic locking mechanisms or a dedicated framework like ShedLock.

The concepts discussed in the post are posted in my GitHub repo at sathishjayapal/runswithshedlock.

This project demonstrates how to use ShedLock for distributed task scheduling and showcases different concurrency patterns for background jobs.

The Distributed Conundrum: Transactions vs. Race Conditions

Before diving into solutions, let’s clarify the problem. In a microservices architecture running on Kubernetes:

- Distributed Transactions occur when a logical operation requires updates across multiple independent data stores or services. For example, when you delete a GarminRun object, you delete and read it in the same transaction. This process is used by various pods. Ensuring atomicity (all or nothing) across these disparate operations is the hallmark of a truly distributed transaction. Failure to manage these correctly can lead to partial updates and an inconsistent system state.

- Race Conditions In a Kubernetes environment, this manifests as multiple pods trying to update the same database record. These updates can happen at the same time. Multiple instances of a scheduled job also kick off concurrently. The issue here isn’t necessarily about multiple logical operations but rather the execution order of concurrent operations on shared resources.

The challenge lies in diagnosing which scenario you’re facing. A seemingly intermittent data anomaly will result from an unhandled distributed transaction or a race condition that needs proper synchronization.

Spring Boot: A Solid Foundation

Spring Boot provides an excellent foundation for building robust microservices. Its strong support for transactional management, particularly @Transactional, is invaluable. Nonetheless, in a distributed environment, the default @Transactional annotation guarantees atomicity within a single data source. But that is a performance drag, too. So, as we called out, the transaction scope is limited to micro-transactions when doing distributed transactions.

Leveraging Hibernate Locks for Data Consistency

Hibernate’s locking mechanisms are incredibly powerful. They are essential for scenarios where you must ensure data consistency at the database level. This is particularly important within a single service instance.

- There are two popular transaction lock, well known in the industry, that you can take advantage of in hibernate.

- Optimistic Locking: We mostly prefer this for the read operation. In the debase, we use it for fetching 100 records that are slotted for deletion.

- When there are multiple data integrity requirements, always prefer Pessimistic locking. In concurrent situations like this, where multiple PODS try to update the data, this is a better choice. Nonetheless, the nature of this causes some native database dependencies as well. So, when there is a need for strong data integrity requirements, I prefer the shedlock framework with “mini transactions.”

By strategically applying optimistic and pessimistic locks, you can effectively resolve many race conditions. This ensures that your service operations stay consistent, even under heavy load.

ShedLock: Conquering Concurrent Scheduled Tasks

Sometimes, the “race condition” isn’t about concurrent database updates but about concurrent execution of scheduled tasks. Imagine a cleanup job that needs to run once every hour across all your Kubernetes pods. Without proper coordination, multiple instances of the job run at the same time. This will lead to redundant work or even data corruption.

This is where a framework like ShedLock shines. ShedLock provides a distributed lock for scheduled tasks. It operates with shared storage, like a database, Redis, or ZooKeeper. This setup ensures that only one instance of a scheduled task can be executed at any given time. It works across all your application instances. This is an elegant solution for:

- Ensuring singleton execution of cron jobs or scheduled tasks.

- Preventing redundant processing in event-driven architectures.

- Managing shared resources that should only be accessed by one instance at a time.

Diving into the Code: ShedLock and Beyond in runswithshedlock

Runswithshedlock project illustrates two strategies for managing concurrency in background jobs. The application is set up with Spring’s @EnableScheduling. It also uses @EnableSchedulerLock(defaultLockAtMostFor = “10m”). A JdbcTemplateLockProvider is configured to use your PostgreSQL database for managing locks.

Here is the class, that calls a method of bulk DB insert of around 10,000 records

Scheduling: This task is set to run every 50 seconds (fixedDelay = 50_000).

ShedLock in Action: The @SchedulerLock(name = "processGarminRunBulkUpdate") annotation is the key. It tells ShedLock to guarantee application synchronization. Regardless of how many instances of your application are running, only one instance will acquire the lock named “processGarminRunBulkUpdate.” This instance will execute the method at any given time. The LockAssert.assertLocked() line provides a runtime check that the lock was successfully obtained.

Task Logic: The garminRunService.bulkUpdate() method in this project creates 10,000 new GarminRun records using Faker data. For a task that generates new data, it’s crucial to ensure single execution with ShedLock. This measure prevents massive data duplication and integrity issues.

@Component

public class ProcessGarminRunBulkUpdate {

// ... constructor ...

@Scheduled(fixedDelay = 50_000, initialDelay = 10_000)

@SchedulerLock(name = "processGarminRunBulkUpdate")

public void processRunEvents() {

LockAssert.assertLocked(); // Ensures the lock was acquired

garminRunService.bulkUpdate();

// Logic to process Garmin run bulk updates

}

}

Parallel work stealing approach

Now, let’s look at me.sathish.runswithshedlock.jobs.ProcessGarminRunCleanupEvents:

@Component

public class ProcessGarminRunCleanupEvents {

// ... constructor ...

@Scheduled(fixedDelay = ONE_MINUTE, initialDelay = 10_000)

public void processRunEvents() {

boolean pendingRuns = true;

while (pendingRuns) {

pendingRuns = transactionTemplate.execute(transactionStatus -> {

List<GarminRun> garminRunList = garminRunRepository.findTop100ByOrderByDateCreatedAsc();

if (garminRunList.isEmpty()) {

logger.info("No more Garmin runs to process.");

return false;

}

garminRunList.forEach(garminRun -> {

garminRunRepository.delete(garminRun);

logger.info("Deleted Garmin run with ID: {}", garminRun.getId());

});

return true;

});

}

}

}

- Scheduling: This task runs every 60 seconds (fixedDelay = ONE_MINUTE).

- ShedLock Absence: This class’s processRunEvents() method does not have the @SchedulerLock annotation. This means that if multiple instances of your application are running, they will all attempt to execute this cleanup task. They will do so at the same time.

- Database-Level Concurrency: This class uses a more granular concurrency control. It operates within its data access layer instead of relying on a global lock. The GarminRunRepository.findTop100ByOrderByDateCreatedAsc() method, which the cleanup job calls, is defined as:

public interface GarminRunRepository extends JpaRepository<GarminRun, Long> {

@Lock(LockModeType.PESSIMISTIC_WRITE)

@QueryHints({@QueryHint(name = "javax.persistence.lock.timeout", value = LockOptions.SKIP_LOCKED + "")})

public List<GarminRun> findTop100ByOrderByDateCreatedAsc();

}

- The @Lock(LockModeType.PESSIMISTIC_WRITE) attempts to acquire a write lock on the retrieved rows. Critically, the @QueryHint(name = “javax.persistence.lock.timeout”, value = LockOptions.SKIP_LOCKED + “”) instructs the database to skip any rows that are already locked by another transaction.

- Concurrency Philosophy: This pattern enables a “work stealing” or “shared work queue” model. Multiple instances of the cleanup job can run concurrently. Each instance will try to fetch and delete a batch of 100 runs. If another instance locks some run objects, they are skipped, and the current instance processes the subsequent available unlocked runs. This approach is highly effective for tasks involving the processing or deleting of independent items from a shared pool. It allows for parallel execution without contention. This maximizes throughput.

The Power of Both, Guided by Design Principles

I’ve found that a combination of these approaches, coupled with sound design principles, is the most effective way to tackle distributed transaction problems:

- Pinpoint the Scope: Clearly distinguish between operations requiring truly distributed transaction coordination. Differentiate those from primary race conditions within a single service. Find cases involving parallelizable work, where Hibernate locks or ShedLock are more applicable.

- Embrace Eventual Consistency: Strict ACID properties across multiple services can be overly complex and impact performance for many distributed scenarios. When possible, favor eventual consistency patterns (e.g., using message queues for inter-service communication).

- Leverage Domain Events: Design your services to emit domain events for significant state changes. This allows other services to react asynchronously, reducing coupling and making it easier to manage distributed workflows.

- Strategic Locking: Apply Hibernate locks judiciously. In the code base where we are deleting their records, I specifically chose the SKIP_LOCKED attribute. PODS can compete for the same batch of data. They can still process record deletes in parallel. They can do this successfully.

- Dedicated Distributed Locks for Tasks: Use ShedLock or similar distributed locking libraries. This is demonstrated in the runswithshedlock project. Utilize these libraries specifically for managing the execution of scheduled tasks. They are useful for any operation that must be singleton across your distributed instances.

By understanding the nuances of distributed transactions and race conditions, I’ve been capable of turning around some exciting distributed problems. Complementing this understanding are the robust capabilities of Spring Boot. Hibernate locks provide precise control. ShedLock offers distributed coordination. The runswithshedlock project serves as a practical blueprint for these patterns. It’s a journey of continuous learning and careful design. With the right tools and principles, distributed systems can be robust and reliable.

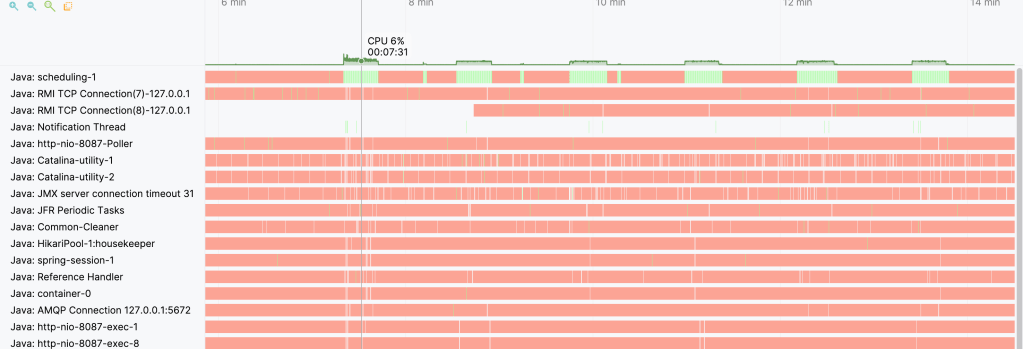

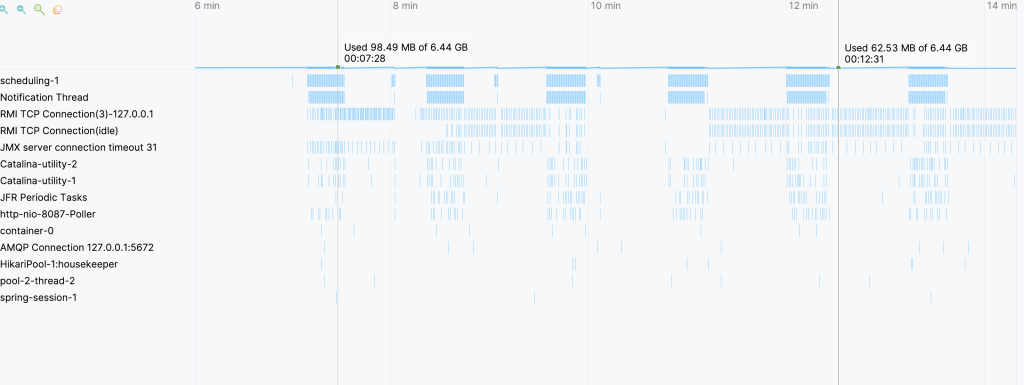

The screenshot of this finally impacts the CPU time. It also affects memory time. This occurs when running and deleting 10,000 records between these two frameworks.

You must be logged in to post a comment.